Programs

Computers are dumb. Sure, they can do some things that we mere humans can barely understand. For example, they can multiply the numbers 159374930 and 43849593 faster than you can read the answer. They can perfectly remember the words in millions of books, while we humans can have trouble memorizing a single page of “Cat in the Hat.”

But that doesn’t make computers smart. They do exactly what they’re told, and nothing more. If you tell a human “walk to the store and buy a loaf of bread,” the human will figure out that you need to put your shoes on, grab some money, look both ways before crossing the street, and actually bring the bread home after you buy it. A computer would need to be told each and every one of those things.

To make it worse, computers don’t speak English. They don’t speak Chinese. They don’t speak any human language. They speak something called machine code, which is just a bunch of ones and zeros (also known as binary). Machine code just does boring things like “add two numbers together” or “load up some information from your memory.” And we humans don’t much like dealing with those boring details, much less deal with them in ones and zeros. We like to think in words and bigger concepts.

But you’ve seen your computer do “smart” things. You’re probably reading this on your computer right now. And you’re not reading ones and zeros, you’re reading words on a page. You’re able to use your mouse to scroll up and down. If you get bored reading this (I don’t blame you), you can go play a game or watch a movie. How do computers do these smart looking things instead of just doing math?

The answer is programs.

What is a program?

Computers only understand machine code. Programs are a bunch of machine code that tell the computer to do something more intelligent, usually to make it easier for a human to interact with it. By interact, I mean communicate with the computer. For example, asking the computer to add 5 and 7 is difficult with machine code. However, I bet you can open up a calculator on your computer right now, click on “5”, then “+”, then “7”, then “=”, and get an answer (though I also hope you can do that math without a computer).

That calculator you opened isn’t magic. It’s a program. It provides an interface to humans to be able to tell your computer what to do. In this case, the interface is a bunch of buttons on the screen you can click with your mouse. An interface provides a human a way to communicate with the computer.

I’m guessing you’re reading this on a web page right now. You view web pages in a program called a web browser, like Firefox or Chrome. This is another program that tells the computer what to do. Behind the scenes, this program is sending messages to computers all over the world asking for web pages, and then turning those web pages into text and colors that you can look at, read, and click on.

These programs are graphical user interfaces. You (the human) are the user. The program provides an interface, something for you to interact with. And it’s graphical: with colors, windows, mouse interactions, and so on.

Text user interface

Before graphical user interfaces existed, there were text user interfaces. These allow you to type in commands as words instead of clicking on things. This still isn’t machine code; you’re still interacting with a program, which is translating what you’re saying to the computer. But let’s go ahead and do some of this now.

NOTE These instructions are intended for Linux and Mac users. They probably won’t work on Windows.

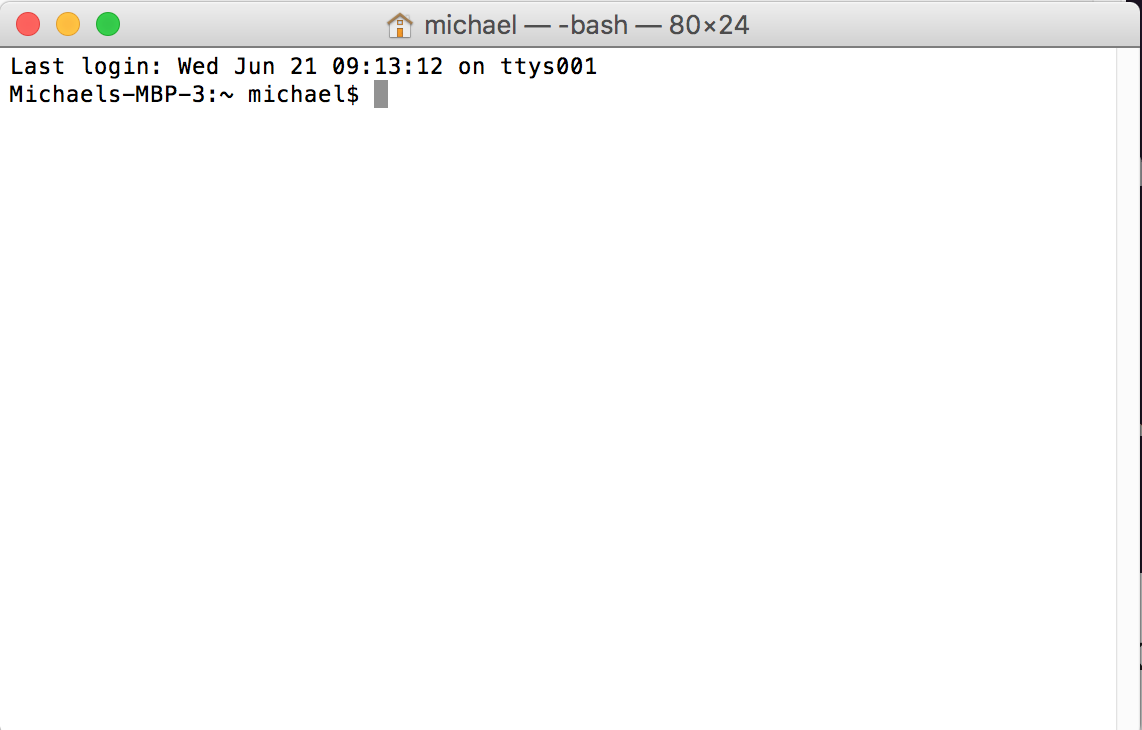

Your computer has a program called a terminal, which will provide a window to run text-based programs in. Go ahead and open it up (ask someone for help if you need it). On a Linux machine, you can usually do this by holding the CTRL and ALT keys on the keyboard and then pressing the T letter (for Terminal). On a Mac, hold “control” and press the spacebar, type “terminal”, and hit “enter”. It should look something like this:

Terminal

Your terminal is running another program inside of it already, called a shell. The shell speaks its own language which is sort of like English, but not quite. You communicate with the shell by typing in commands and hitting enter. This is also known as the shell’s input. The shell communicates back with you by putting things on the screen. This is also known as the shell’s output. To demonstrate, try typing in the following and then hit enter:

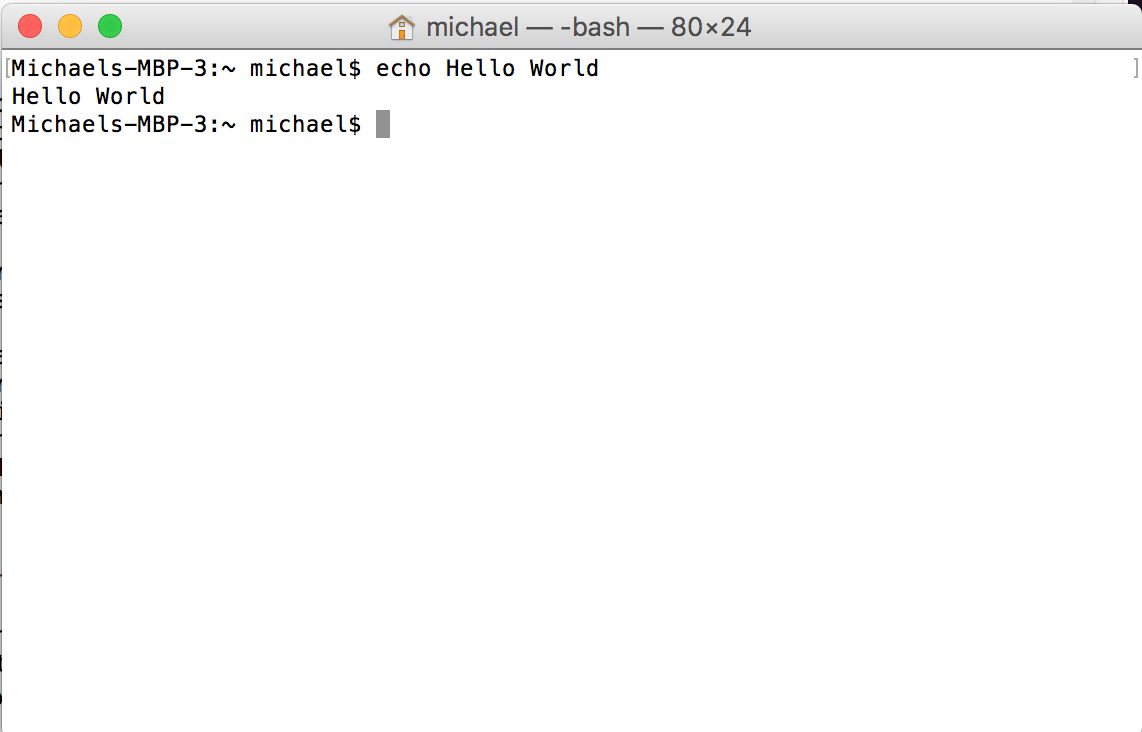

echo Hello WorldThe shell should say “Hello World” back to you (like an echo… get it?). It will look something like this:

Shell Hello World

The way the shell works is that the first word you type in is a command, like echo, and the rest of the words are arguments, like “Hello” and “World”. You’ve said to the shell “run the command echo, and give it the arguments Hello and World.” The shell responds to the command echo by running a new text-based program called echo with the arguments Hello and World. And the machine code in echo knows that it should print those words back out.

Want to try another? Try typing the command date. It should give you the current date and time. Wait a few seconds and run it again, and you should get slightly different output.

You can even download web pages with the terminal. Want to go to YouTube? Try typing in curl https://www.youtube.com. This won’t look like what you’re used to seeing, it’s just a bunch of weird letters, numbers, and symbols. That’s what the web page looks like inside. Your web browser has been converting it to something easier for you to interact with.

Question What program did you run to look at YouTube? What argument did you give to that program?

So why do we care about these text interfaces when we have such better graphical interfaces today? Why would you ever run date if your computer just shows you the time already? What possible use does echo have? And why would I download a webpage like that when I could actually watch a video in my browser?

The answer is that the shell is very powerful, and allows us to do some things that are difficult or impossible from a graphical interface. If you only ever use a graphical interface, you’re limiting what you will be able to accomplish. And when it comes to programming, many things are much easier to do with the text interface.

Exercise Type in bake a cake. What happens? Why do you think that happens?

Silly calculator

Our shell can do some special magic itself. For example, you can use it as a little calculator. Try typing in the following:

echo $((5 + 3))Tada, you have a text based calculator! It turns out that a shell is more than I’ve told you already; it’s a complete programming language. A programming language is a language that allows you to write your own programs. What’s cool about the shell is you can write some really simple programs right in the terminal, like our mini calculator.

There are lots of different programming languages out there. You may have heard of some of them: Javascript, C++, Python, and Ruby. You may be wondering why there are so many different programming languages instead of just one. Let me ask you a question: why are there so many different human languages, like English, French, Spanish, Japanese, and Russian? It turns out there are lots of reasons for this. Each programming language does things a little bit differently.

In this magical guide, we’ll be talking about a programming language called Haskell. Since this will be the first programming language you learn, I’m not going to tell you what makes it different than other languages, because that would just be confusing. Treat it as another piece of magic for now. After you’ve learned Haskell, you can learn other languages and see how they’re different, just like how once you know English, you can learn Hebrew and see how different it is (weird! the letters go right to left instead of left to right!).

With shell, I said you could write some simple programs right in the terminal. But if we want to write real programs, we probably don’t want to have to type the whole program in on a terminal each time we want to use them. So instead, we usually write programs into files. Which brings us to our next section…

Exercise Can you get the terminal to tell you what 43 times 22 is?

How the shell looks

You may have noticed that when you type things into the shell, it already says something on the screen. On my computer, it looks something like this:

Michaels-MBP-3:~ michael$This is called the prompt, and it tells you some things, like the name of the computer you’re on, and the name of the user. You don’t need to worry about that stuff. Everything up until that dollar sign ($) is just information you can ignore.

A lot of the time, you’ll see instructions that look like this:

$ echo Hello WorldYou don’t actually type in the dollar sign; it’s just there to tell you that that’s a line you type in your shell after the prompt. This makes more sense when you see it with the output:

$ echo Hello World

Hello WorldBecause the first line starts with a dollar sign, I know that it’s what I typed in. And since the second line doesn’t, I know it’s what the shell says back to me.